Two years and a day

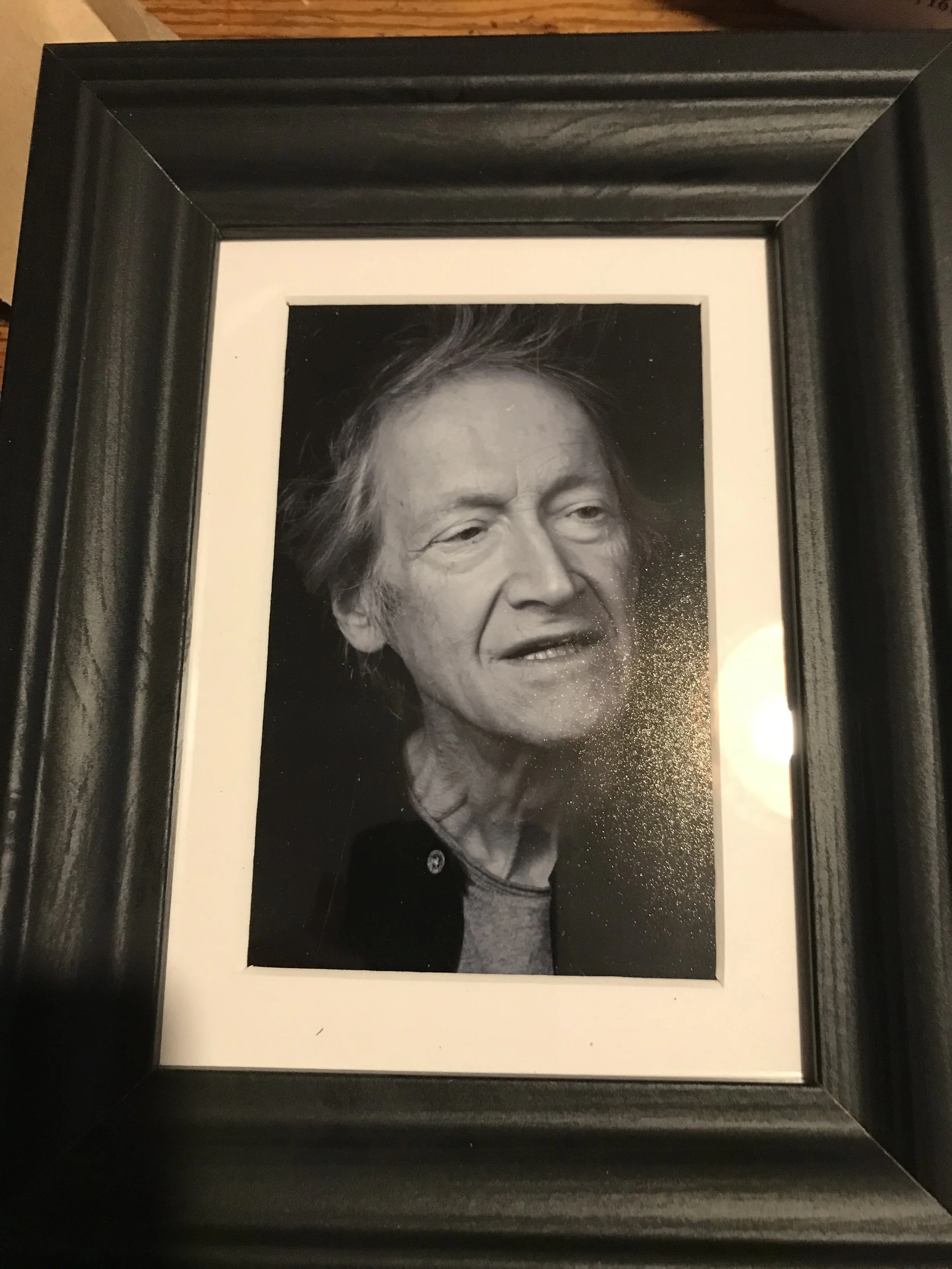

Two years and a day ago, 200 people gathered in person on a blazing hot day at Kensal Green cemetery (with more attending online) to say farewell to my father, Michael Horovitz.

It was a beautiful gathering. John Agard read a poem, Karyl Nairn and the late, lamented Niall McDevitt spoke. Niall overran a little. There were hecklers. I got to (gently and politely) overrule the Rabbi and let Niall finish. Vanessa, Michael’s partner, blew his kazoo as if it were a Shofar.

It was as much like one of my father’s gigs as you could hope for. A little mayhem, a heckle or two, kazoos, poetry, love.

Below is the text of what I said on the day.

It feels unbelievable to acknowledge that we are gathered here to say farewell to my father. It is agonising to have to accept that there will be no more sung answerphone messages or dizzy glissandi of greetings in the street or at his door, no more trading of puns in the midst of deep conversations, no more fierce debates or loving exchanges, no more gleeful recitals of You Are Old Father William by Lewis Carroll to leaven arguments.

Michael (which I always called him after a brief period, aged two or so, of calling him Michael-Daddy) seemed indomitable, even at his frailest. His will to live and to enjoy life certainly was indomitable - he enjoyed the thrill of it, and every opportunity to extend his part in it. He loved the people it brought to him, who he wooed and teased and disagreed with and loved with an ecstatic fervour.

There were, of course, many Michaels - we all experienced different parts of him at different times.

There was the refugee child, youngest of ten siblings who escaped Nazi Germany when he was two, the family’s bridge to the new land of Britain who took the new accent as if born to it, who put on shows with his siblings in the houses they were evacuated to and fought off bullies who mocked him for being both German and Jewish - Hardpunch Horrorfist, they called him at school.

There was the descendant of rabbis and poets who took the family tunes and religious words and fused them with Bebop and Blake, and more, to create a body of work that bounced the multitudes it contained around with a joyous and ecstatic thrill of creation, which was underpinned with a deep and all-embracing seriousness.

There was the impresario and editor who brought together poets of the stage and page with musicians and numerous other art forms in the fiercely held belief that all the arts should work together to keep the flame of creation alive.

There was the seeker after new voices, the generous motivator of unsung voices and ideas, driven by a young and flexible mind that was still excitedly planning new things and new possibilities, even unto the last day of his life.

There was the husband and lover who adored the women in his life, even after sorrow and departures and changes of circumstance: particularly Anna Lovell, my mother Frances Horovitz, Inge Laird and, in the last 11 years of his life, Vanessa.

There was the son, who adored, and was awed by, his parents, even as he rebelled against the tenets of their faith; who honoured them as best he knew how to the end of his life. The youngest brother whose siblings meant more to him than he was sometimes able to express. The madcap uncle, delighting his young nephews and nieces with a frisson of chaos and laughter.

And then there was the father. I will revel in the memories of his glee and tenderness, the way he used to do star jumps in the lane whenever my mother and I left in the car, the invented words and sound games that punctuated our life, the way he played all three Billy goats Gruff to my tiny troll under a bridge near the house I grew up in, our rambling discussions about family and poetry (which were so often intertwined, in conversation as in life), the many confidences and shocks of growing up alongside this mercurial, loving man, as the only child of a single father.

I will remember our disagreements, of the sort to be expected within any family who lived cheek-by-jowl after early grief, but I will remember more strongly, and with an unreservèd joy, their resolutions - which, though they were sometimes slow to bear fruit, always bore the sweetest apples of knowledge. And, even more strongly, I will remember how much I love him.

Michael was without doubt a complicated man, but he always a loving one. His interests were wide-ranging, heterodox, sometimes conflicting and quixotic, but even in the depths of conflict, he sought out tender resolutions. While not all of these resolutions were achieved, he was always firmly of the belief that if, as Blake suggested, he told his wrath to friends, the wrath would end, and if they told him theirs, the same.

Though he was not a practising Jew, having (as he once joked to me) practiced quite enough as a teenager, the faith he was raised in acted as a bedrock to all of his adventures in life, a jumping off point. He put his faith in poetry, and in people; in the beauty of language and how it can effect change. He helped bring the Underground overground, raised his head above the parapets of the ivory towers of Oxford, and elsewhere, and kazooed until the walls tumbled enough to let people out and in more freely.

His was the Judaism of Woody Allen and Leonard Cohen, Chagall and Kurt Schwitters, Harold Pinter, Paul Celan and Mel Brooks. A child of his times, reaching adulthood in the midst of post-war austerity, he was driven by a need to escape strictures and rules and be free, and always, always welcome others into that freedom.

I see now, so clearly, how deep the seams of him, and what I have learned from him, run within me. This has been made more apparent by the fact that we had not seen one another during Covid, for nearly 18 months before his accident - the longest time in my adult life that we had been apart. The last time I saw him, on the penultimate day of his life, as I was being forced to leave by the hospital staff, he clutched my hand and said: “I hadn’t realised until now how much I’d missed you.”

In these last two weeks, those seams of him in me have become a deep, abiding comfort - because it is only now that I realise how much I had missed him, and just how much I always will.

And so will so many people, whose lives he touched, whose art he championed, whose songs he helped them find the freedom to sing.

Here’s, then, to my father, Michael Horovitz. Long may his words, paintings and songs, and the artistic freedoms he fought for, live on.